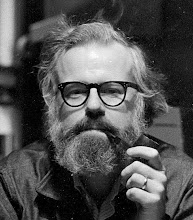

John Hess and James Reston

From the archives: February 2, 2004

Reading John L. Hess's My Times: A Memoir of Dissent is abundantly gratifying. Nothing more gratifying, because bias-affirming, than his memories of James Reston (I can't call him "Scotty," for I didn't know him). Reston, the ultimate insider and toady, LBJ's useful Polonius ("LBJ occasionally consulted Reston on how his Vietnam policy would play and found him 'quietly approving' ((see Robert Dallek's Flawed Giant))," Reston, who was unfailingly able to deceive himself that he'd always opposed American policy in Vietnam, right from the very start.

Reading John L. Hess's My Times: A Memoir of Dissent is abundantly gratifying. Nothing more gratifying, because bias-affirming, than his memories of James Reston (I can't call him "Scotty," for I didn't know him). Reston, the ultimate insider and toady, LBJ's useful Polonius ("LBJ occasionally consulted Reston on how his Vietnam policy would play and found him 'quietly approving' ((see Robert Dallek's Flawed Giant))," Reston, who was unfailingly able to deceive himself that he'd always opposed American policy in Vietnam, right from the very start.

"I do not question Scotty's sincerity," Hess writes, "That is how Scotty remembered it now." Then, "Scotty's writings contradict his recollection."

How was Reston able to do this, to write one thing, and to believe he was writing another? That's a question I was asking forty years ago. I wrote the following satire in the Spring of 1965. It was after reading yet another of Reston's "the mood in Washington" pieces:

From the Berliner Zeitung

April 14, 1942

"The Mood in Berlin"

by Reinhold Restonschmidt

There is a strange mood in Berlin these bright Spring days. Although the skies are blue, and the trees and flowerbanks along the Kurfurstendam are blossoming, the beer gardens are all but deserted, and strollers talk in hushed undertones. Indeed, there is an unseasonal bleakness in the air, and one hears phrases like "the winter of our discontent." Nor is it just the appearance of RAF bombers in our skies---in itself an ill omen. It goes much deeper than that, and is difficult to express, this new mood of the capital. It was put in a phrase, superficial but succinct, by a Hamburg reporter a few days ago. "People here have lost their old confidence," he said. The bright promises and the astonishing victories of three years ago are things of the past. Moscow, which only a year ago seemed within our grasp, is more distant than ever. And the recent entry of the Americans into the war, degenerate though they undoubtedly are, must give the seasoned observer pause. This chastened mood pervades the Reichschancellory itself, and is shared even by the Fuhrer. His old ready optimism is gone.

The average German citizen, spared the agonies of decision-making, cannot really begin to imagine the pressures that have been placed on the Fuhrer by events both at home and abroad in the past few weeks. Whether Adolf Hitler spends his days in the bustling offices of the Reichschancellory, or tries to find a few hours of peace and quiet in the mountain fastness of his beloved Bavaria, decisions must be made, new problems confronted daily, opposing counsels listened to. And finally, in the quiet of his nights, the bitter truth must be faced: he, Adolf Hitler, and he alone, must decide. No wonder then that the Fuhrer has been irritable and somewhat short of temper with the Berlin press corps.

Among the many problems confronting him is the pace of the Final Solution. Some advisers, particularly those in the S.S. under the determined Heinrich Himmler, have been openly critical of what they regard as the slow pace of F.S. They have charged that Zyklon B gas is simply not being produced in suffricient quantities to be effective. Some officers charge openly that they are being hamstrung, and these complaints are being echoed in the Reichstag. Not content with the liquidation of Jews, Gypsies, and elements hostile to the Reich, they are now demanding in increasingly strident tones that the Solution be extended to the degenerate Slav race as a whole. The eastern front, they assert, will not be safe until all traces of this blot have been eliminated.

On the other hand, the Fuhrer is assaulted by pleas that liquidation be sharply curtailed. Some high officials, particularly those in the Ministry for War Production and Forced Labor, charge that the Final Solution, while perhaps noble in conception and lofty in aim, is proving counter-productive. They cite statistics, some of them very persuasive, showing that labor battalion quotas simply cannot be fulfilled unless the Final Solution is slowed down. One harassed labor official expressed his exasperation to me recently. It was all very well, he said, for S.S. General Kurt von May to speak of "gassing the Slavs into eternity," but the general was not responsible for wartime production. Moreover, many officers on the Eastern Front privately express their disgruntlement with the zeal of S.S. Kommandanten in their areas. How are peasants th to be won over to a new life, a new loyalty, they ask, when great numbers of them are being shot, hanged, or gassed in the name of Race Purity?

Thus the Fuhrer is being assaulted by sharply conflicting advice, and with every day that passes, the lines of care seem to be etched ever more deeply in his face. He betrayed his apprehension last week in a meeting of the Weestphalia mayors' conference when he lashed out against "defeatists" and "those who would doubt the Reich." "We have no use," he said, with obvious anger, "for the man who panics at the sight of the first bomber in the sky."

But there is no doubt that a decision must be made, and made soon, regarding the Final Solution, and no one understands that fact better than the Fuhrer himself. Few quarrel with the ultimate objectives of F.S. But an increasing number wonder openly if it is not being pushed too quickly and if the Fuhrer, with his well-known impetuosity, is not the victim of his own high intentions. Thus Berlin waits in suspense. Only when he decides one way or the other will the old confidence return.

<< Home